Visitors entering the State Rooms of the University of St Andrews are currently confronted exclusively with oil portraits of the University’s past principals and chancellors. To diversify the exhibition, the University Museums and the School of Art History initiated a collaboration: students of the module “The Portrait in Western Art”, under the supervision of Dr Elsje van Kessel, proposed works to update the exhibition. This text is the shortened version of my proposal. I suggest adding seven photographs to the exhibition – six portraits of pioneers of early photography and one self-portrait of the photographer Franki Raffles (1955–1994). These objects are among the highlights of the roughly 30,000 prestigious photographs in the University museum’s art collection.

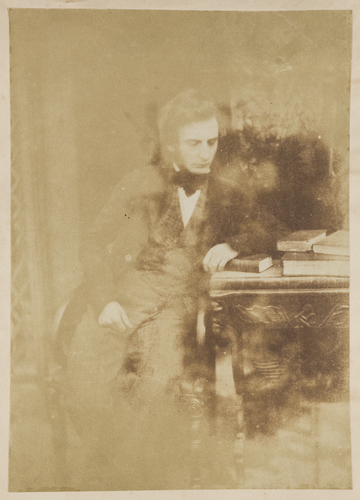

The first set of photographs shows prominent members of an intellectual circle of photographers and scientists in St Andrews, which developed under the leadership of Sir David Brewster (1781–1868), back then principal of the United Colleges of St Andrews University. Brewster knew William Henry Fox Talbot (1800–1877), the inventor of a photographic process called calotype, and encouraged his circle to master this highly complex process and to refine Talbot’s invention through collaboratively conducted experiments. Since Brewster persuaded Talbot that patenting his invention in Scotland would be unprofitable, the St Andrews community could experiment with Talbot’s invention for free. The calotype was also a matter of scientific publications. Many pioneers were members of scientific associations like the British Association for the Advancement of Science and the St Andrews Literary and Philosophical society. Most of these personalities held prestigious positions at the University. For instance, James David Forbes (1809–1868) succeeded Brewster as the principal of the United Colleges, Dr John Adamson was a doctor and chemistry professor (1809–1870), and Hugh Lyon Playfair (1787–1861) the University provost.

Images Courtesy of the University of St Andrews Libraries and Museums

In contrast to these amateur photographers, other personalities were University alumni who decided to work as professional photographers – among the first world-wide! One of them, Robert Adamson (1821–1848), produced artistically important photographs in his Edinburgh studio in collaboration with the painter David Octavius Hill (1802–1870). A second photographer, Thomas Rodger (1832–1883), opened a purpose-built professional studio in St Andrews in 1849, nowadays housing the University’s Careers Centre. The selected photographs commemorate these pioneering figures and provide examples of early portraits produced with the calotype process.

Courtesy of the University of St Andrews Libraries and Museums ID: ALB-24-2-2

I propose to juxtapose this set of photographs with a self-portrait by the feminist photographer Franki Raffles. Raffles, born in England, studied philosophy at the University ofSt Andrews starting in 1973. During her studies, she took a leading role in the local group of the Women’s Liberation Movement. As a member of this group, she fought against gender inequalities within the University and proposed radical changes to the movement’s organisation and aims. After her degree, Raffles taught herself the art of photography and worked in Edinburgh as a freelance photographer. In the 1980s and early 1990s, she travelled through Scotland and Asia to document the harsh realities of women’s everyday lives and thus raise public awareness of the everyday problems of women. In 1992, she led the “Zero Tolerance campaign”, a successful initiative against domestic violence. For this project, she designed posters including photographs of women in apparently normal domestic environments but bearing inscriptions indicating that these women were victims of abuse. Why is Raffles’ link to St Andrews important for understanding her art? Although Raffles was not yet acquainted with photography during her studies, in St Andrews she developed many of the feminist ideals which later pervaded her photography. On 17 October, photographer and St Andrews alumna Franki Raffles would have turned 67 years old.

Courtesy of the University of St Andrews Libraries and Museums, ID: 2014-4-1699-6a

Raffles’ self-portrait would add another aspect to the display. It stands for female empowerment, as it depicts Raffles in the act of taking her own picture. As a result, she retains control over her identity and is not objectified. Furthermore, juxtaposing the portrait of one woman with those of six men would visualise the historical gender imbalance at St Andrews University. In fact, for centuries women were not accepted at the University as students, let alone as professors or principals. Likewise, the portraits of personalities from Brewster’s circle include only men. Although women actively participated in the early development of photography, they were forced into less prominent roles than men due to social conventions. For instance, they were active in scientific associations but could not become official members, and they often worked as assistants of male photographers without being acknowledged.

The proposed selection of photographs would also diversify the artistic mediums represented in the current exhibition. This would allow visitors to compare the oil paintings in the State rooms with the newly added photographs. For instance, Brewster would be shown in both media. Formally, the representations are similar, with Brewster sitting on a majestic chair, along with books symbolising his erudition, and holding glasses in his hand, a possible allusion to his scientific contributions in the field of optics. But there are differences too: Brewster’s individual characteristics stand out more clearly in the photograph than in the oil painting. At the time, calotypes were usually taken outside, where the sun provided enough natural light. As a result, photographs often featured a spotlight on the depicted figure, which here highlights the details of the sitter’s face and hands. Moreover, the portraits differ in scale. While the oil painting is large and majestic, the photograph is small and more intimate. The new medium would then also allow showing new facets of Brewster’s personality. In the current context of the State Rooms, Brewster’s oil portrait honours him in his role as a principal. In the context of other pioneers of early photography, Brewster’s portrait would commemorate his additional role as a scientific leader and promoter of photography.

The State Rooms are meant to represent the University. The proposed display would provide a more comprehensive picture of its history, indicating its pioneering role in the early history of photography. And why not enjoy the contrast between majestic oil paintings and intimate photographs?

Written by Francesco Alessandrini Lupia, 4th-year student in the School of Art History of the University of St Andrews