The University of St Andrews portrait collection was established to commemorate important figures in national and institutional history. However, a walk around Parliament Hall or the Senate Room, two of the University’s State Rooms containing the most venerable portraits of the collection, does not show the full story. Women were fully admitted to the University in 1892 and many figures worked hard to improve educational opportunities for women, but they are not on display and their histories are therefore hidden from the narrative. There is currently only one portrait of a woman on display, despite the fact that the University currently has a female Principal and Rector and sixty percent of the student population is female. How can we best diversify the collection and commemorate those who have made a difference?

‘Portraiture’ for most people brings to mind large, old fashioned oil paintings, an idea which the current display supports. However, it can be found in many more forms including in sculpture, photographs, banknotes and all over social media. As well as diversifying the people represented, it is important that the State Rooms better present the various forms of portraiture in the University collection, including photography and sculpture. I have selected three portraits which bring to light hidden narratives, depicting figures who worked hard to allow women a university education at both St Andrews and across the country.

Image courtesy of University of St Andrews Libraries and Museums

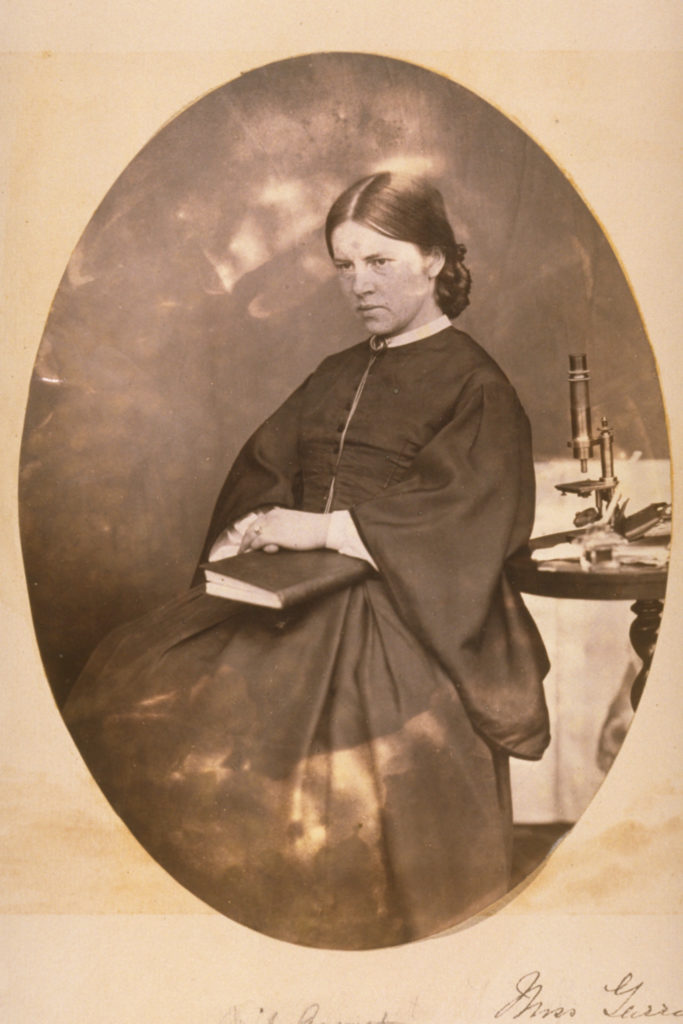

The portrait of Elizabeth Garrett Anderson (1862–63) was taken by photographer John Adamson and can be found in his Playfair Album of the 1850s and 60s. In 1862, Anderson matriculated to study medicine, but once the board found out she was a woman, she was no longer allowed to study at the University. Anderson did not let this stop her, going on to become Britain’s first female doctor and working tirelessly to improve opportunities for women in medicine across the country, co-founding the New Hospital for Women and the London School of Medicine for Women. Although Anderson has more recently been recognised by the University for her efforts, her story is still obscured by other important medical alumni such as Edward Jenner who invented the smallpox vaccine.

Anderson’s portrait also serves to highlight St Andrews’ important place in the early history of photography. John Adamson (1809-70) was overshadowed in history by his brother Robert, despite making Scotland’s first calotype photograph, a portrait, in 1842. His photograph of ‘Miss E. Garret’ uses motifs traditionally used in male portraits to show intellect, unusual at this time for a portrait of a woman. Anderson wears a plain, dark, button-down dress and holds a book, showing her desire to learn. In the background of the photograph sits a microscope on a wooden table, which she faces away from, just as she was refused an education. Importantly, she avoids any eye contact with the viewer of the portrait, showing her shame and frustration. Photographs create a stronger sense of truth than painted portraits and are more familiar to modern day viewers, who are constantly surrounded by photographs on social media.

Image courtesy of University of St Andrews Libraries and Museums.

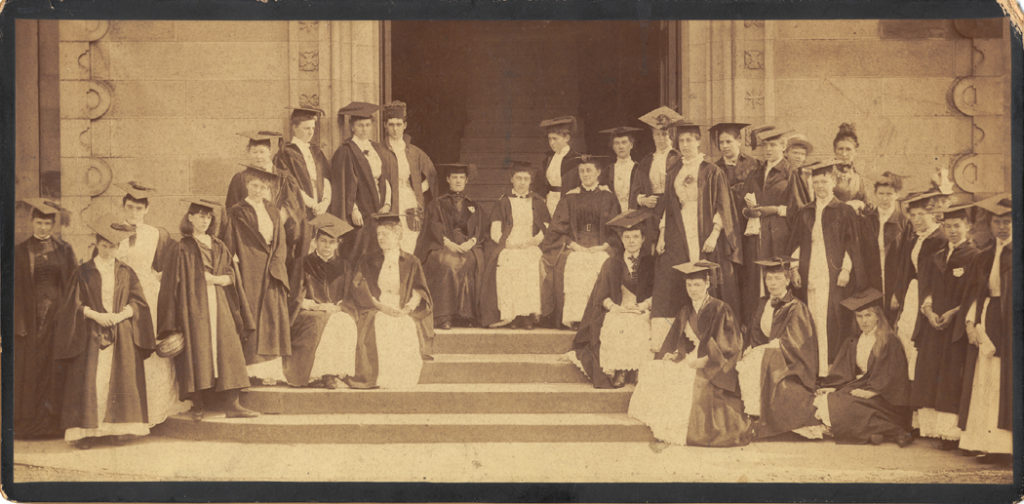

Other photos in the University archive commemorate women who, thanks to the efforts and determination of Elizabeth Anderson, were able to graduate from St Andrews. A photograph by an unknown artist shows a group of female graduates in St Salvator’s quadrangle (1896) and the woman on the left is likely Agnes Blackadder, the University’s first female graduate. Blackadder graduated in March 1895 and became a dermatologist before working for the Scottish women’s hospital during the First World War. Without Anderson’s rejection and determination, Blackadder and other women may never have been able to study at the University.

Courtesy of the University of St Andrews Libraries and Museums, ID: HC196

The third portrait shows Professor William Angus Knight, LL.D. (1892) who became a professor of Moral Philosophy at St Andrews in 1876. Just one year later, he established the ‘Lady Literate in Arts’ (LLA) programme which offered university-level courses on a range of subjects and continued until 1931. Although the programme has been criticised for its distanced-learning approach, which made sure women would not mix with male students in classes, the programme was an important step towards female education. By 1892, women were allowed to study full time under an act of parliament and in 1896, the first female hall of residence in Scotland was built with funding from the LLA, University Hall. Knight also donated 139 framed portraits and eight portrait busts to the University collection which he believed would help to read students about the character of those portrayed, true also of his own portrait.

The artist, Elizabeth Hean Alexander (1862–1951), has left little trace in Scottish art history and shows determination at a time when it was still difficult for women to obtain artistic training. The State Rooms only have the work of one other female artist on display, Victoria Crowe, and once again her work is overshadowed by famous artists such as Henry Raeburn and David Wilkie.

Although the painting appears traditional, showing Knight’s power through his large body and direct eye contact, he is not intimidating, instead coming across as thoughtful and meditative with a relaxed pose. The artist has created visual unity through the red crest, book and drapery, the key symbols of the portrait. The crest in the background is the unofficial University arms used before 1905 and designed by St Andrews librarian, James Maitland Anderson. Including the crest in the portrait recalls the rich history of the University and ensures Knight’s place within this.

Both Elizabeth Anderson and Professor Knight were resilient and determined figures who sparked change at the University and throughout society. Including their portraits in the State Rooms would bring to light their untold stories and help the display to more accurately represent the current community’s beliefs and ideals.

Freya Irving, 4th-year student in the School of Art History of the University of St Andrews