“You’ve got to know your boxes” I was once told by a photographer, meaning you’ve got to know what you’re photographing and what ‘box’ the images will go into. Then, once those boxes fill up, you may have the start of a project or a collection. The boxes could contain anything, portraits perhaps, or photographs of football culture, or images of shipbuilding, but in general for ‘boxes’ think themes.

In late 2020 I contacted Rachel Nordstrom, then Photography Collections Manager at University of St Andrews, with a question about different types of boxes. I wanted to know about best practice for the archiving of negatives, of prints and contact sheets. What type of archival boxes should I be looking at to store negatives and prints in, and was there a best practice way of doing that, of listing the contents to those boxes? How does one turn one’s collection of images into an archive? I thought if anywhere knew, it’d be the University of St Andrews where they’ve been collecting photography since its birth in 1844.

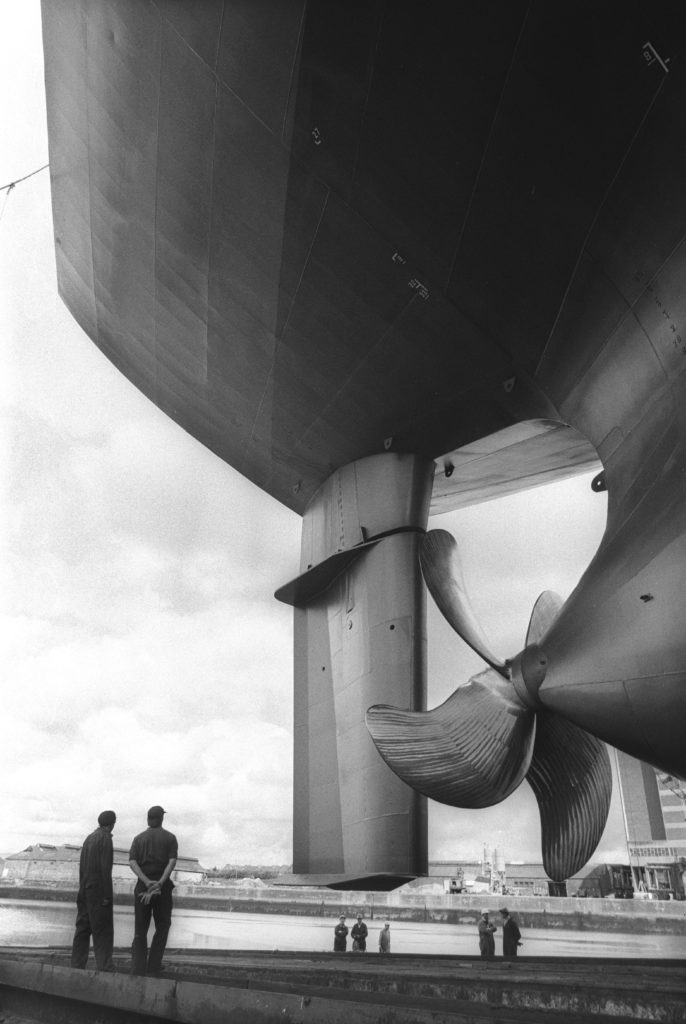

My own collection of photographs that I’ve taken dates back roughly to 1988, from my college years in Glasgow where I studied photography, and from trips in summer vacations to the Middle East. Those were my first footsteps in photographing and travelling, and from those travels I began to think I could use photography as a tool to let me explore our world. Never did I think it would lead me to the adventures I’ve since had.

Over the following 30+ years until now I’ve been fortunate that my photography career has been kind to me and it’s taken me around the world to multiple countries, where I’ve been afforded opportunities to meet people from all walks of life, from the man in the street down on his luck to royalty, from cultural icons to household names from the world of business, and not only in the UK but with opportunities to gain insights into cultures the world over. And all the while I was photographing it all, documenting it all, hoping one day it would find a home.

This has led to a large collection of photographs, many taken on assignments for newspapers and magazines, corporate and NGO clients, but also many taken on self-initiated projects. Overall, my collection of photographs now sits at roughly one million digital images, that’s the RAW shoots, edited down it’d be far less of course. And, from the earlier days of my career there are the thousands of rolls of negatives, with accompanying contact sheets, prints, and tear sheets of much of the published works.

With the opportunities I’ve been afforded, the moments I’ve witnessed, there comes a certain responsibility to then care for the resulting images. What use are they if they sit in my office, unseen? I owe it to the people I’ve been fortunate enough to meet, those who offered me glimpses of their lives and let me photograph, to tell their stories, to share the resulting photographs with others. If others then find merit in the work, then perhaps it will all mean something, perhaps the photographs can help break down barriers across the world between differing peoples and cultures.

To share those images also carries the responsibility of looking after them, making sure the prints won’t get torn, the negatives won’t curl, and fade and the hard drives of digital files won’t get corrupted. Was keeping them in my office the best place, or would they be better placed in a facility geared and aimed towards best archival practices for photography? A place such as the temperature controlled archival facility at University of St Andrews.

As Rachel Nordstrom and I discussed boxes, and archiving workflows, we began discussing the housing of my collection within the University’s prestigious collection of photography of Scotland, and of the world by Scottish photographers. We both felt it would be a natural fit.. There was cross over between some of the projects I’d worked on and work already within the University collection, thus adding to the research and educational potential for all the work.

Importantly for me the scale of the St Andrews collection, and of their aims and ambitions for their collection, also fitted with my desire to keep all of my archive in one place. I had no desire to split my work up amongst varying institutions who would take one project, or two, but ignore the rest. I felt there would be merit in keeping it all together, thus a more rounded portrait of a working photographer’s life and career could be utilised by those who wished to view it, to hopefully find merit in it and the imagery and information it contained.

Bringing order to my collection was first and foremost, but during Covid pandemic lockdowns it was a good use of my time, sorting, annotating, adding information, and bringing enough order to the work that it would be in a position to be understood by others. I always hoped my archive would be acquired by an institution, but I imagined it 20 or 30 years from now, at the end of my career. It’s been a little surprising it has happened now, but I think all parties are all the better for it.

Now, as the University works with my photography and uses it for the common good and educational benefits, I’m on hand to add information, to answer questions when they arise. I get to see my work utilised, and we get to collaborate to jointly extrapolate more worth from that which I have photographed. Importantly I also don’t have to burden my family with looking after it all, making sense of it all, should something happen to me.

Now that my collection is housed in St Andrews, birthplace of Scottish photography, I feel slightly freed up to look forward more easily to all the things I’m yet to experience and photograph. The sorting of my collection this past year or two involved a lot of glancing in the rear-view mirror, and while the work is undoubtedly now in a better place for it, looking back too much can bring certain feelings of nostalgia or melancholy perhaps – one side effect of preparing the archive that no one warned me about was the emotional aspect of looking back over it all. But perhaps that is a topic for another blog post.

For now, let us jointly celebrate that my archive of photography has joined the already important and impressive archive the University has built. I look forward in coming times to exploring my work with the researchers and academics, teachers and students, and perhaps in further blog posts I can share the stories behind some of that which I’ve photographed, the cultures I’ve seen and the people I’ve been most fortunate to meet along the way and who graciously let me photograph their lives. The celebration of the archive is primarily the celebration of the stories of all these people, without whom there would be no photographs, and no archival boxes to fill.

Written by Jeremy Sutton-Hibbert © Jeremy Sutton-Hibbert 2022.