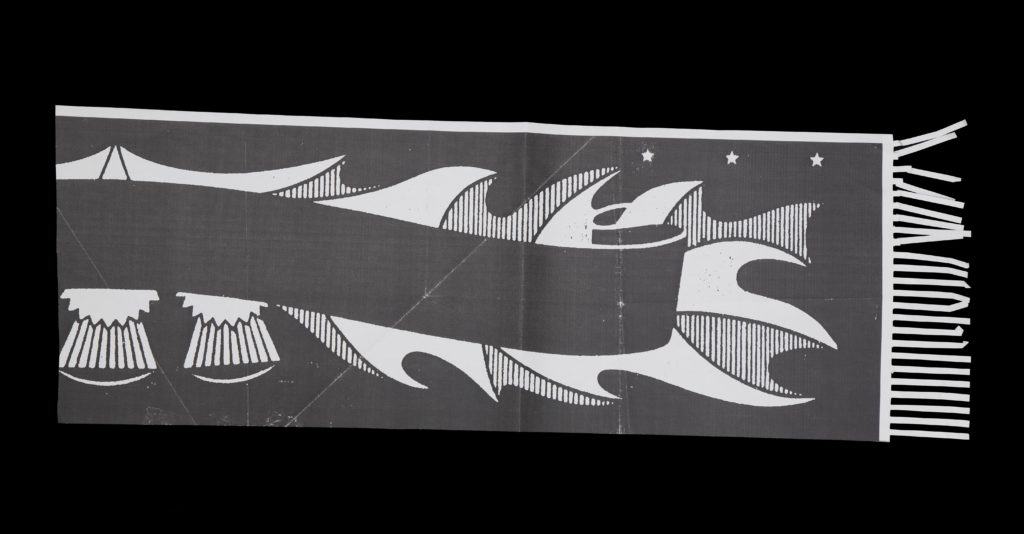

The Scotsmanless scarf is a remarkably concise object. Fabricated out of supple grey and black lambswool, the piece features the historical masthead of The Scotsman newspaper reimagined in the form of a football scarf. The graphic simplicity of the pattern, inverted from recto to verso, resembles in no small measure the contrastive black-and-white layout characteristic of historical newspaper printing. The Scotsman was founded in the early 19th century as a radical liberal paper that set itself against what it regarded as privilege and corruption. Broadly supportive of parliamentary reform, regional self-determination, and transparency, the newspaper grew increasingly prominent in the decades that followed and eventually came to occupy an iconic Edwardian building in central Edinburgh.

The history of the newspaper serves as a kind of shorthand for broader changes wrought by economic modernisation over the course of the 20th century, not only to once-thriving Scottish industries but also to a broader marketplace of information. Over the course of the 19th century the paper—a longstanding voice of Scottish political liberalism—was quick to adopt new technical innovations such as the electric telegraph in 1866 and the use of a rotary printing press in 1872. More recently, this has included the decline of hot metal typesetting and attendant introduction of computers into the production process in 1987, followed by the launch of a website in 1999. The significant contraction of print media in subsequent decades has seen The Scotsman’s geographic displacement from the centre of Edinburgh and its material downscaling from a broadsheet to a compact tabloid size whose smaller format is better suited to use by commuters. It is tempting to read these forms of contraction and displacement as emblematic of broader decline in the power of prestige print media and of traditional regional information ecosystems. The original remit of The Scotsman had been to expose local forms of corruption and malpractice; it seems deeply suggestive that the paper’s subsequent headquarters in Holyrood Road were recently taken over by a Scottish video game maker, which trades in highly immersive, fictive digital media environments.

Of course, the text of the paper’s name is conspicuously missing from the masthead in Scotsmanless. Instead, the motif frames the subtly variegated fabric of the lambswool itself. Here another history comes into view: that of the weaving industry that thrived in mid-19th century Scotland. The scarf was made in collaboration with Begg x Co, which, like The Scotsman, dates to the 19th century. And, like the paper whose masthead it partially reproduces, the scarf is very much a product of regional Scottish histories of labour and technology. The company was founded by Alex Begg in 1866 in Paisley. The Scottish town was the centre of the weaving industry in Victorian Britain and was famed for its production of textiles bearing the Persian and Indian teardrop motif now synonymous in the English-speaking world with its name. In the early 19th century, highly skilled Paisley weavers were known for their political radicalism and their influential support of reform during the economic downturn that followed the Napoleonic Wars. The weaving industry was also notable for its inclusion of women, who had traditionally done a great deal of spinning and who made up more than half of the industrial cloth production workforce by the middle of the century. The Scottish textile industry was — and still is — particularly vulnerable to shifts in consumer behaviour and international supply chains. By the time Begg x Co was founded, many of Paisley’s mills had already gone bankrupt in response to both the economic crises of the 1840’s and the later disruption of the cotton supply brought about by the American Civil War in the 1860’s. The company relocated to Ayr on the west coast in 1902 and the last of the Paisley mills closed in 1933.

To an extent, then, the Scotsmanless scarf is a product of two of the foremost industries of 19th century Scotland, industries particularly embedded within a tradition of radical progressive politics. Animated by steam-powered rotaries, the printing press and the power loom were agents of economic modernisation and political reform that were deeply rooted in Scottish regionalism. Rather than read Scotsmanless as a eulogy for these industries, though, we might think about how their histories are revived and refashioned into a new kind of living object. The piece remains a product of highly skilled Scottish labour but one whose mobility and mutability can accommodate a much more diverse set of identities and lived practices.

Author Details:

Stephanie O’Rourke is a lecturer in art history at the University of St Andrews. Her research focuses on 18th- and 19th-century European visual culture, particularly in relation to scientific knowledge, spectatorship, and media technologies.