Ever heard of Charles Darwin? What about A.R. Wallace? Although he is the lesser-known of the two, A.R. Wallace made significant contributions to the field of natural science and the theory of evolution. Volunteer blogger, Vanessa Silvera, writes about his life and work, and where you can find his personal collection of taxidermy birds of paradise.

The Bell Pettigrew, St Andrews’ natural history museum, is home to several splendid specimens including, but not limited to, fossil fish, glass sponges, Narwhal tusks, and a plethora of extinct species. Visitors may also notice a handful of exquisitely colourful birds on display, acquired by the museum in the late nineteenth century. Unbeknownst to many, these ‘birds of paradise’ originally belonged to scientist Alfred Russel Wallace whose contributions to evolutionary biology remain largely overlooked.

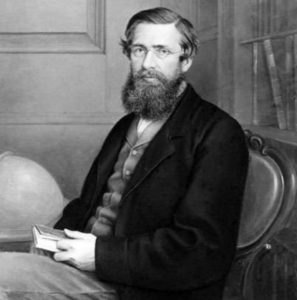

A.R. Wallace was an extraordinary individual, a man of great talent and strong convictions. He is best remembered as an influential naturalist, explorer, collector, and most significantly as the co-founder of the theory of evolution along with Charles Darwin.

Born in 1823 in the Welsh countryside, A.R. Wallace was one of nine children, and his appetite for learning began at a young age. As a boy his family moved to Hertfordshire, England where he attended school until he had to leave at the age of fourteen. Despite this setback, Wallace was determined to continue his education. He read treatises, studied maps and attended lectures by social reformer Robert Owen, all of which played a role in shaping his beliefs. In the meantime he worked at his eldest brother’s surveying business for a few years until 1844 when he accepted a teaching position in Leicester. He quickly befriended fellow amateur naturalist Henry Walter Bates who introduced Wallace to entomology, the study of insects.

In 1848, the two men decided to venture overseas to the Amazon to observe and collect the region’s flora and fauna. Wallace studied and gathered an impressive collection, primarily beetles, butterflies and birds. Tragically, on his return home, his ship sank and nearly all his research was lost. Undeterred, however, Wallace embarked on another voyage, but this time to the Malay Archipelago (present-day Malaysia and Indonesia).

From 1854 to 1862, he collected more than 125,000 specimens, over 5,000 of which were previously unknown to the western world. One night in 1858, while ill, Wallace had an epiphany: that natural selection is the driver of evolution. Within populations, variations are found among individuals. Individuals with traits better suited to their environment survive, reproduce and pass those traits to their offspring. This was a highly controversial theory because it was at odds with the Bible, which states that the Earth and its species remain unchanged since creation. Shortly thereafter, Wallace wrote to his hero Charles Darwin about his discovery. Darwin, impressed with Wallace’s work and similar to his own, included his paper in his publication On the Origin of Species (1859).

Following his departure from the Far East, Wallace went back to England as an esteemed member of the scientific community. He continued to devote himself to his scientific and social pursuits. Over the span of his lifetime, he published 21 books as well as over 1,000 articles and letters. What set him apart from his contemporaries was that he was a spiritualist and social critic. He disagreed with the notion that natural selection accounted for human intellect and supported unpopular causes including women’s rights and land nationalization. Though he was outshone by Darwin, Wallace did receive recognition for his work. He was granted a number of awards and honorary doctorates from the Universities of Dublin and Oxford in 1882 and 1889 respectively.

Around 1885, some of Wallace’s most prized taxidermy treasures made their way to St Andrews. Dr. Albert Günther, Keeper of Zoology at the British Museum, presented samples from Wallace’s private collection to William McIntosh, the Director of the Museum. McIntosh acquired 46 ‘birds of paradise’, including the stunning Quetzal, multiple bright-feathered Pittas, parrots, hummingbirds, and many others, which are accessible for public view.