The Bell Pettigrew Museum is part of the Museums of the University of St Andrews and it is located in the Bute Building in St Mary’s Quadrangle on South Street.

At the Bell Pettigrew we have a number of rare and extinct animals. It is crucial that we safeguard these specimens for any potential research opportunities. Respecting the museum by only consuming water and monitoring the environmental conditions, means that the specimens stand a better chance of maintaining their good condition. We wanted to share a few of the interesting oddities in the collection with you.

The Resplendent Quetzal (Pharomachrus mocinno) is found at high altitudes in Central American cloud forests and is extremely rare. The great taxonomist Albert Günther , who was Keeper of Zoology at the Natural History Museum in Kensington, presented the striking specimen to the Bell Pettigrew Museum.

Spotting the difference between male and female quetzals is simple because during breeding season the males grow a pair of tail feathers that can be 1 metre in length. Sadly, due to their beautifully coloured feathers, quetzals are hunted resulting in a severe decline in numbers and this is not helped by a continued loss of their cloud forest habitat. It is almost impossible to keep a quetzal in captivity as they tend to die quite quickly upon capture and for this reason, quetzals are used as a symbol of liberty in the Americas.

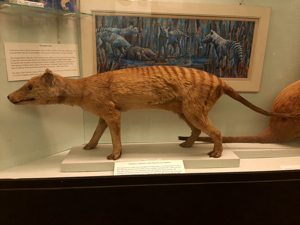

Moving to the other side of the world across Australia and New Guinea is where one would have found the Thylacine or Tasmanian wolf/tiger (Thylacinus cynocephalus). Thylacines were the world’s largest marsupial predator, but their numbers went into decline with the arrival of humans 40,000 years ago. By the time Europeans arrived the Thylacine was extinct in New Guinea, almost entirely eradicated from Australia and was largely confined to the island of Tasmania.

Due to issues with sheep farming, the Tasmanian government introduced a bounty of £1 for every Thylacine killed with the last recorded wild Thylacine being shot in 1930. The last captive Thylacine died in 1936 in Hobart Zoo and despite being quite a common animal at one time, little is known about the biology of this fascinating animal. Despite almost certainly being extinct, there have been numerous reported sightings of ‘dog-like creatures’ in Australia and in September 2016 a team of British investigators from the Centre for Fortean Zoology released a video of a potential Thylacine sighting in Adelaide.

The Bell Pettigrew Museum is a fantastic place where you can learn about a variety of wildlife both great and small – and everything in between. But we don’t need to tell you how great it is; Sir David Attenborough visited in 2011 and commented: “Packed full of treasures and wonders, the Bell Pettigrew is a spectacular reminder of how important a museum can be in the study of the natural sciences”.