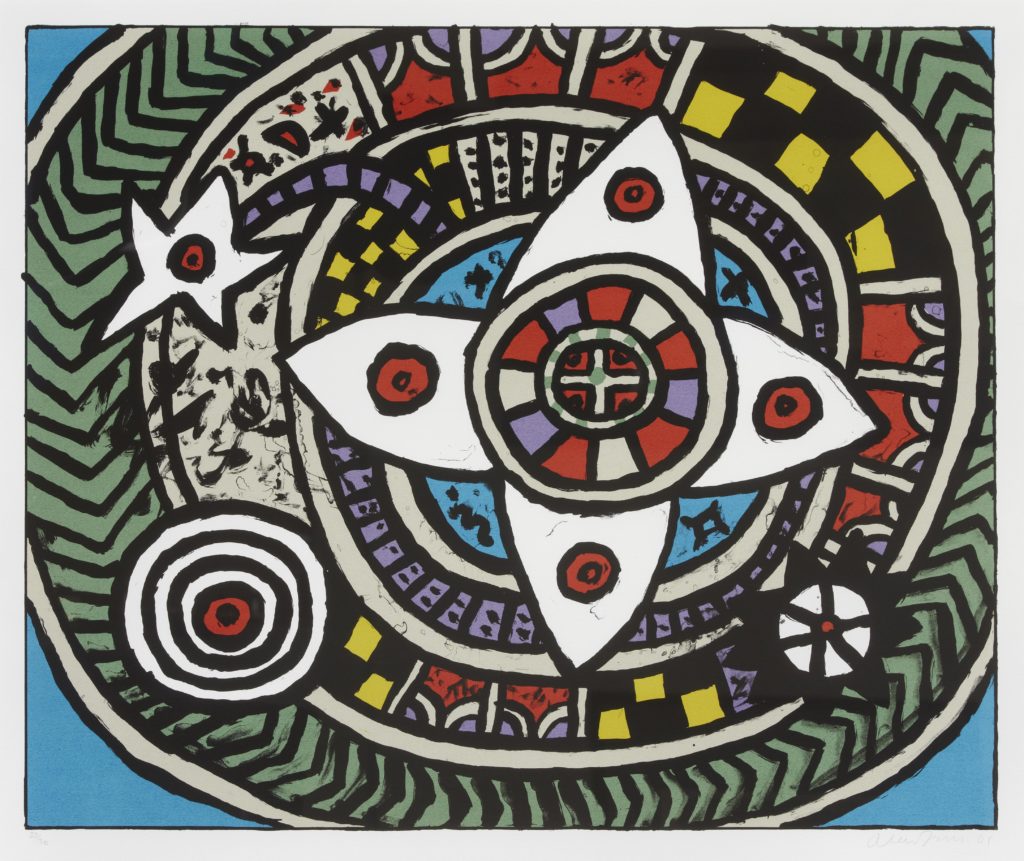

Zurich Improvisations XII, Alan Davie, (HC2001.14), ©The Artist’s Estate

‘All of them were filled with the Holy Spirit and began to speak in many tongues as the Spirit enabled them.’ The Acts of the Apostles, Chapter Two, Verse Four

‘I don’t practise painting as an Art but a means to enlightenment.’ Alan Davie, Towards a Philosophy of Creativity, Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art, Edinburgh,1997

Zurich Improvisation XII is one of a series of 34 lithographs that Alan Davie (1920-2014) produced in 1965. He had only recently taken up printmaking and initially worked with Stanley Jones at his newly set-up Curwen studio in Cornwall. Almost from the outset Davie preferred to produce his prints in serial form which was in keeping with his drawing practice. His highly experimental approach to printmaking was to make spontaneous marks and improvised drawings directly onto the lithograph plates. Then he would get the printer to run them off on different presses, introducing areas of transparent colour and printing the plates the right way up but sometimes upside down. By using this highly improvised way of working, Davie radically freed up the usual order and practice in mechanised graphic printing. This allowed him to respond to, and build on, any stimulating accident and unforeseen occurrence, that might emerge.

Such was the keen interest within the printmaking fraternity with Davie’s innovative approach that he was soon invited by the prestigious printmakers, Editions Alecto to work with them. This included a visit to Zurich where Davie produced his ‘landmark’ Zurich Improvisations – of which the Boswell Collection’s Zurich Improvisation XII is a fine example.[i]

By this time, Alan Davie had built a national and international reputation with important works of his in the Tate, London and MOMA, New York collections. He had also gained the award of the Sao Paulo 1963 Biennale Prize for best international painter. Davie was not however, particularly concerned with his reputation within the art world. He always saw his art as having, and serving, a different purpose than the pursuit and acquisition of worldly success.

A student at Edinburgh College of Art (1937-41), where he felt he learned very little that was of use to him, Alan Davie gave up art during his war service. Even after his return to civilian life he preferred music, poetry and jewellery-making, while earning his living as professional jazz musician. However, on a belated travelling scholarship trip to Europe in 1948-9, Davie rediscovered his love of art. Furthermore with the encouragement of Peggy Guggenheim, whom he met at the Venice Biennale in 1948, the long-term support of Gimpel Fils Gallery and the appointment to an art teaching position from fellow Scot, William Johnstone, Principal of The Central School of Art, Davie found his main creative outlet to be painting again.

Cosmic Signals No. 1, Alan Davie, Courtesy of the University of St Andrews Libraries and Museums, ID: HC2004.23(3)

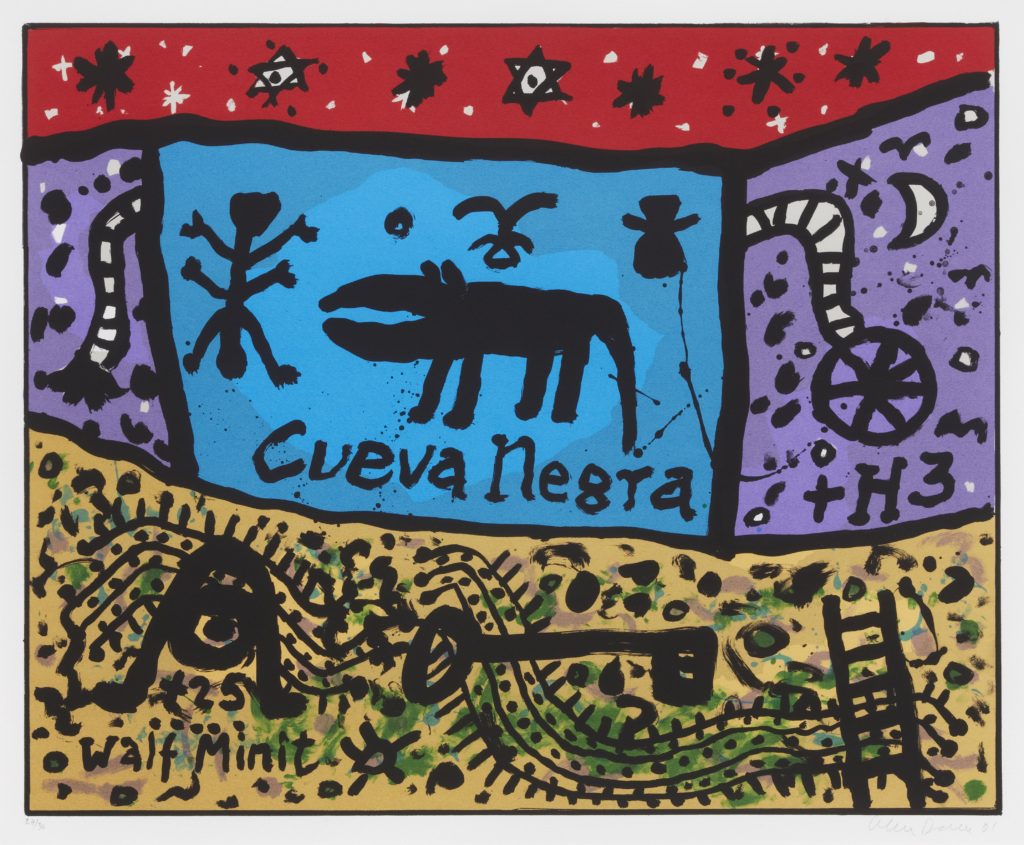

Cueva Negra, Alan Davie,

Courtesy of the University of St Andrews Libraries and Museums, ID: HC2004.23(2)

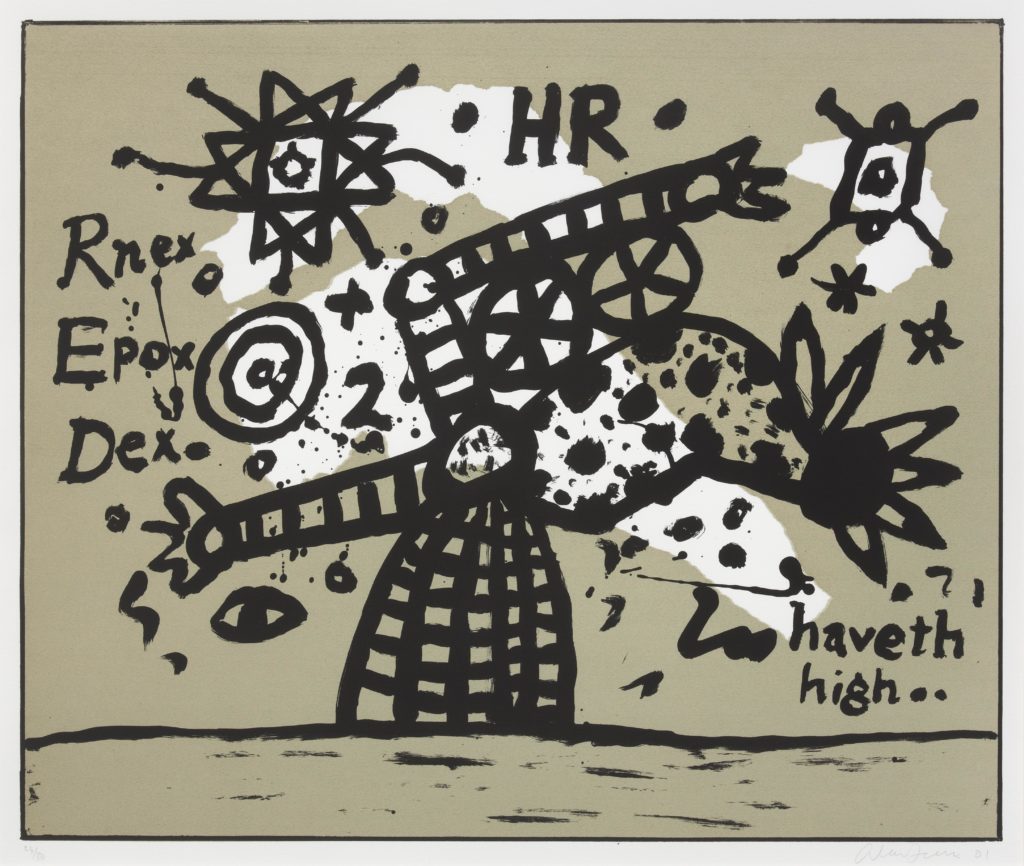

Haveth High, Alan Davie,

Courtesy of the University of St Andrews Libraries and Museums, ID: HC2004.23(4)

The 1950s was an exciting time for young emerging artists like Alan Davie, when the practice of painting was opening up to radically new approaches in content and technique. The most influential innovation was Jackson Pollock’s all-over method of working with the canvas spread on the studio floor. Davie followed this example, but for a very different purpose to Pollock’s ‘drip painting’. Unlike the American Expressionists Davie felt that ‘self-expression is something contradictory to Art.’[ii] He did not wish to impose his own emotional personality on his painting and turn it into an autobiographical ‘event’. Rather, like the tribal shaman, he sought to lose the controlling power of the ego over his actions, This then would allow the spiritual forces of cosmic creativity to pass freely through him as he immersed his whole being in the intuitive and spontaneous process of laying paint down on the canvas lying out before him. As he said, ‘If a work is to be of any value it must convey something that transcends the material.’

Along with the development of his absorbing art practice, Alan Davie also sought out sympathetic support and rapport for the deeply spiritual purpose of his art. He found this in a range of sources, for example, in the spiritual exercises of the Japanese Zen Masters and also in the alternative philosophy of the psychiatrist Carl Jung. Davie was particularly taken with Jung’s concept of the Collective Unconscious where the transcendental language of archetypal symbolism is seen as a universal one. With this Jungian cosmic concept Davie could link his own psychic and artistic revelations with the earliest and far flung traces of human language in the form of tribal and religious symbols and communal pictographs. Thus Davie’s art looked to evoke, the same spiritual intensity and cosmic communication as that which he found in the wide range of religious cultures he sought out in his readings and travels. These included Byzantine iconic mosaics, Pictish iconography and early Christian illuminated manuscripts, then later in Tantric mystic symbols and Jain esoteric imagery.

Scottish art for a variety of socio-historical reasons has produced little or no religious art since the Reformation. This makes Alan Davie a rare, if not unique, figure in Scottish modern art in having a deeply, all-pervasive spiritual dimension to his work. In many ways he is closer to earlier religious artists/craft persons when he says for example, ‘I paint to find enlightenment and revelation. I do not practice painting as Art.’ Davie used his art to ‘conjure up the unknowable’ and reveal the divine spirit in all things, as has been the case with all great religious art – from Palaeolithic cave painting to modern Theosophists like Kandinsky and Mondrian.

The Zurich Improvisations suite of lithography prints is a wonderful demonstration of how Alan Davie infuses spiritually expressive power into his art. His use of the series format echoes such Christian art examples as the Twelve Stages of the Cross and the Seven Sacraments. However, instead of having a linking illustrative chronological narrative, Davie’s highly abstracted prints are simultaneously interconnected by the repetition and variation of boldly outlined symbols and vibrant splashes of luminous transparent colour. Each print sings out with its own visual voice, but together, the whole series becomes a glorious multi-chromatic anthem, like a great cathedral stain-glass rose window.

[i] An illustration of the complete Zurich Improvisations series is to be found in the catalogue for Alan Davie, Work in the Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art, National Galleries of Scotland, Edinburgh, 2000, (Fig. 92)

[ii] All the quotes of Alan Davie are from Notes by the Artist, in the catalogue of the Alan Davie, retrospective exhibition, Whitechapel Art Gallery, London, June, 1958

Author Details:

Bill Hare is an Honorary Fellow in Scottish art history at the University of Edinburgh. He has written extensively on Scottish modern and contemporary art and has recently published Scottish Artists in the Age of Radical Change-1945 to the 21st Century, Luath Press, 2019.