Introduction

The University of St Andrews are the caretakers of collections which span the entire history of the University, from the documents recording its foundation in 1413 up to the acquisition of the Prince Wullie, previously found in St Salvator’s Quad.

Not only important to the documentation of our university’s history, the collection remains a vital resource in teaching. Additionally, this year we were looking forward to finally opening the doors to the new Wardlaw Museum and to bring a small sample of this collection to the fore, with new objects, new interpretations, and a fresh lick of paint to boot!

Unfortunately, due to the COVID-19 crisis which has turned all our lives on their heads, people will have to wait a little longer to view the displays. Even more critical, access to the collection for teaching in its current state was limited, and the usual status-quo of hands on learning with collections has been interrupted.

Behind the scenes during this whole crisis, a team of people in IT have been working with the company Mnemoscene to create an online tool, Exhibit, which allows for a narrative-based approach to exploring 2D images and 3D objects. This has presented Museums a new avenue for allowing access to the collection; not only will the collection be available online, people will be able to use the tool to create their own narratives and explore the collection in a way unique to them.

With this great opportunity has come an all new challenge for the team at Museums. How can a small team scan over 100,000 objects and make them available online? The simple answer? We can’t. However, we can make a start, with a commitment to integrate digitisation of the collection into our everyday practise. As this period of 2020 has shown, digital is no longer a nice addition, a complimentary side to the main dish of the museum. Having a high-quality digital offer ensures that, even in unprecedented times, the collection in some form can always be accessible.

Museums secured a grant from the Esmée Fairbairn Collections fund to begin a rapid digitisation project to develop and implement a new tool for storytelling-based engagement with digitised collections. In this blog I am going to take you behind the scenes of the scanning process – taking the physical object and turning it digital.

The Scanning Process

The two methods we are employing to digitise the objects are Photogrammetry, using a camera to capture images of an object from multiple angles and stitching them together, and using a 3D scanner, an instrument which scans an object and builds 3D models in real time.

The 3D scanner Museums use is called the Artec Space Spider – it looks like a fancy iron, but it has made the introduction into digitisation a lot simpler!

By taking multiple scans of museum objects and stitching them together in Artec Studio, we are able to produce 3D models ready to be uploaded to our database and made available online. It sounds fairly simple (so we thought back in August) and some objects were. If they have good ‘geometry’ (with lots of unique shapes and features for the program to pick up on) and good ‘texture’ (basically anything not shiny) we can make a model ready for upload in an hour or two.

However, we quickly realised many of our objects do not fit this simple criteria. Our collection has shiny things like silverware (not good), scientific instruments which are smooth and have little uniquely shaped features (not good), or are made of glass (really not good).

The object I will discuss today is an object we thought (naively) would scan well. It is relatively small, has lots of colour and unique shapes for the scanner to pick up – the dream!

The Mouth Ornament

The Mouth Ornament was acquired in the 1830’s by a Captain Brown. It was likely made on the west coast of New Ireland, but was acquired by Captain Brown on the Duke of York Islands, a popular trading post in the area at the time. The mouth ornament is made of boars tusks, dogs teeth, dewarra shells and either glass or resin beads. It is thought it was a war charm, held by clenched teeth by warriors of Papua New Guinea.

Research into the mouth ornament is ongoing, with new information coming to light as recently as April 2020. It was considered a great piece to highlight the potential of the exhibit tool – with a rich history, component parts which each hold significance, and new interpretations which challenge our historic understanding of this object. For this reason, it was an early choice for the scanner!

Scanning the ornament

We came to scan the object, and I personally was very excited as it is one of my favourite objects in the whole collection. We placed it carefully on the table and got to scanning! Early on we thought we were on to a winner, the boar tusks were picked up beautifully by the scanner, and the criss-crossing beads across the tusks, despite being small, were also showing up well!

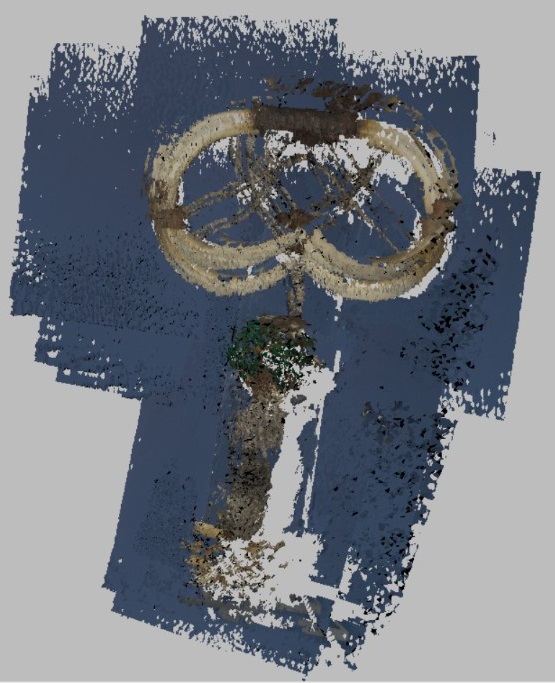

However, the beaded tassel then came into view. When we scan, the model can occasionally exhibit what is called ‘noise’, where the light emitted by the scanner reflects off the object’s surface and creates a haze around the objects. The tassel was not just noisy, it was a whole firework. Still we persevered, as we can usually deal with noise in the post-processing stage by erasing unwanted elements.

We thought the beaded part of the tassel was bad, but then we reached the dogs teeth finial. I should mention at this point, the scanner also does not handle sharp points, thin edges or points very well. The dog teeth were all of these, as well as shiny. Needless to say, it was not picked up well at all.

Still we endured with the scans, in the hope we’d be able to salvage it in post-processing. During post-processing, we clean up the model by removing any unwanted elements, such as the table base and the aforementioned ‘noise’, we align the scans as best as we can then run the ‘autopilot’ function which does a lot of clever computer things to stitch it together into a final product.

We tried our best, we really did, but have you ever tried to differentiate one dog tooth from another? Find which green bead on one scan lines up with the green bead on the second, third and fourth scan? Needless to say, despite all our ambition, we were not able to get a complete model of the mouth ornament though our Spider Scanner. The best we could offer by the end of the day was a well modeled top part of a mouth ornament, with the tassel conveniently chopped off by the autopilot.

After approximately four hours of trial and error, we moved it to the Photogrammetry list.

Final thoughts

The purpose of this blog is not to condemn the Scanning Spider and its abilities, for many objects now it has been a great success. More, it is to shed some light on this process and demonstrate its not always plain sailing – technology is very clever, but sometimes it is boggled by a shiny surface. Whilst not quite an Aladdin’s cave of glittering jewels and gold, we have come to realise our collections is pretty shiny, albeit comprising lacquered wooden boxes filled with metal and glass scientific instruments, or silver spoons from students of the past.

Digitisation on this scale is not a quick fix or an instant remedy for this COVID-sized hole we have been left to deal with. We have been fortunate to have a small team who have been able to dedicate their time fully to get some of the collection available in time for teaching. However, it has become clear for Museums that digitisation is a long-term commitment, it needs time and dedication to get a whole university collection online.