The Recording Scotland collection is a set of paintings and sketches collected during World War II to permanently capture the “feeling” of the nation. Each piece of artwork was chosen because it was an essential view of Scotland; with emphasis on the places most likely threatened by war and industrialisation. This is part two of a series of blogs about different aspects of the Recording Scotland collection.

In the late 1940s, James Bell Salmond (1891-1958), a St Andrews alumnus and World War I veteran, was asked by Principal Sir James Irvine to write text to go along with a series of watercolour paintings from the Recording Scotland collection publication.

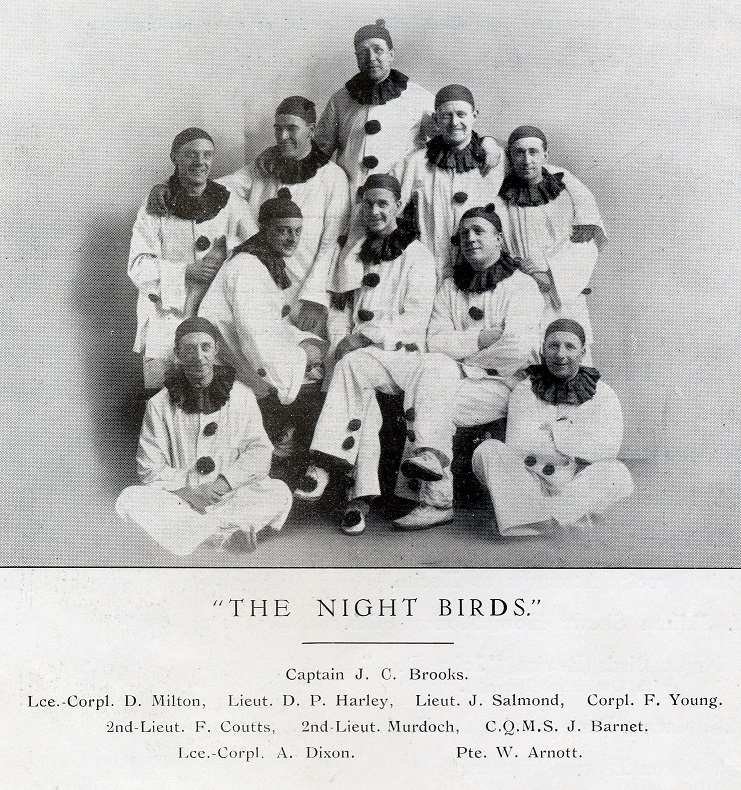

Salmond had been an active student at St Andrews and graduated with a degree in Political Economy in 1913. He began his professional life as a journalist and editor. Not long after, he enlisted in the First World War and saw action on the Western Front and was wounded. At the time he was known for writing poems about his wartime experiences in the Scots dialect and editing the hospital newsletter from his bed. He returned to Dundee to continue editing newspapers and magazines, ultimately establishing himself as a prominent citizen.

When the Second World War broke out, Salmond served with the Homeguard in Dundee and became the Keeper of Muniments (the university’s institutional archive) and the warden of St Salvator’s Hall in St Andrews. Salmond spent time over four decades writing histories of the military and golf, two novels, and his works of poetry. As he liked to put it, he was a “journalist reporting/ A thing or two in rhyme.”

It was not a surprise when Sir James Irvine asked Salmond to write the text that would join several of the Recording Scotland paintings. As Salmond explained he endeavoured to “re-people the pictures.” The stories or vignettes in the book came from the location histories or his own personal encounters across Scotland.

In the early years of the Recording Britain plans, categories for artwork were hoped to capture fine tracts of landscapes, towns and villages, parish churches, and country homes and their parks. We see similar impulses in the Recording Scotland collection, with a distinctly Scottish flair.

The images chosen for the collection do reflect a myth of Scotland during this time period. By not focusing on the modern accents in the images it creates a timelessness, and further promotes an idealised image of society. This nostalgia avoids the distasteful advancement of time and could be used to inspire soldiers and citizens alike to continue the fight to protect the homeland.

Castles can reflect the more majestic history of the nation – defence, wealth and familial ties while churches can reflect the more religious aspects, and the crofts the agricultural industries sustaining the population. Each image can reinforce the traditional values that help influence citizens and improve morale. However, the paintings did not always reflect the grandest locations, but rather the local and obscure places that better characterise life in Scotland.

One of the great ironies in the collection is the very absence of war. The images that were selected avoid documenting in fine detail the presence of the war. Rarely do you see soldiers or military structures. Some of this can also be attributed to difficulties faced by civilians traveling near military areas to receive permission. Many artists lamented bureaucratic red tape as wartime restrictions gave them limited access to areas controlled by the military and navy. This caused some confusion at times and frustration in keeping them from places they wished to paint.

Some of the paintings, by the time they were published, proved that time had indeed overtaken them. “Cat Row, Dunbar” by May M. Brown is one such piece. A picturesque street in the seaside village of Dunbar, known for all the cats that called it home. In 1937 the street, as we see it painted, was demolished as part of the Town Council’s clearance programme and replaced with modern houses.

Salmond in his account laments the loss of the fisher quarters, old cellars, an old pier, the Rock House, and all the cats. He reflects on the once prosperous herring fishing and suggests that the Scottish answer for why the fishing might have failed was because “despite the warnings of the Kirk, Dunbar men would go fishing on the Sabbath.”

Whether it was a cat or a cathedral, the Recording Scotland captured not only the images of the era but many of the thoughts and concerns of the artists and authors that surrounded the collection.

Today happens to be International Cat Day, so in honour of the long gone cats of Cat Row, go ahead and take another picture of your favourite moggy.