The story of Peter Pan is one beloved by many around the world. For students of St. Andrews, his author, JM. Barrie, is held in equally fond regard, as he held the role of Rector in the early twentieth century. Here, Masters’ students in modern literature Sadbh Kellett and Mia Foale talk about his life, works, and time at St Andrews, and what this means to a student at the University today.

The Scottish writer Sir James Matthew Barrie was born on the 9th May 1860 in Kirriemuir, Angus. Barrie was the ninth of ten children to Margaret Ogilvy and David Barrie, a weaver. Barrie was educated from the age of eight at the Glasgow Academy, at ten in Forfar Academy, and at fourteen in Dumfries Academy under the eye of his two elder siblings Alexander and Mary Ann, who were already established teachers. He would read Literature at the University of Edinburgh and graduated with an M.A. in 1882.

Following his university years, Barrie found himself work at the Nottingham Journal. This was also when he began to write stories of the Kailyard Tradition, which established him as a popular and successful writer. These included works such as Auld Licht Idylls (1888), A Window in Thrums (1889), and The Little Minister (1891). However, Barrie’s success in telling stories inspired by his mother’s recollections of her childhood attracted criticism from established writers and critics, who felt that Kailyard representations of rural life were foolish and idealistic, with novelist George Douglas Brown deriding them as “sentimental slop”!

Barrie soon turned his attention to playwrighting, a natural consequence of his enthusiasm for drama and the establishment of a theatrical society when he attended Dumfries. These works also varied in success, with some, such as his biography of Richard Savage, being poorly received, and others, such as Ibsen’s Ghost (1891) a great triumph. It was through this involvement in theatre that Barrie would also meet his wife, Mary Ansell, an inspiration for many of his characters and operatic works. By the beginning of the twentieth century, JM. Barrie was established as a success with a run of notable productions such as Quality Street (1901) and The Admirable Crichton (1902). Now was the time for the character to appear that would make Barrie’s work as timeless as the boy whose story he told: Peter Pan, or the boy who wouldn’t grow up.

Peter Pan first appeared in Barrie’s novel The Little White Bird, but the play Peter Pan, or the Boy Who Wouldn’t Grow Up, presented on the stage in 1904, brought Barrie and his much loved character to the world’s attention. From JRR. Tolkien to George Bernard Shaw, literary greats displayed their enthusiasm for the play that was beloved by children and adults alike. JM. Barrie would later develop the play into a novel named Peter and Wendy (1911) which, true to his passion for combining his literary and social works, he would gift the copyright of to Great Ormond Street Children’s Hospital.

According to Barrie, Peter Pan was inspired by Peter Llewelyn Davies, a son of Barrie’s close friends Arthur and Sylvia. Barrie was incredibly close with the family, naming many characters after their children. Upon the death of Sylvia in 1910, JM. Barrie was left with shared custody of her children, who he would financially support and look after for the rest of their lives, seeing them through school, writing to them daily when they were away and being a steadfast figure in times of uncertainty. Sadly, the boys met untimely and tragic ends, with George dying whilst serving in the First World War, Michael drowning at the age of twenty-one, and Peter later committing suicide. Their legacy lives on in the stories of Peter and the other works that they inspired JM. Barrie to create.

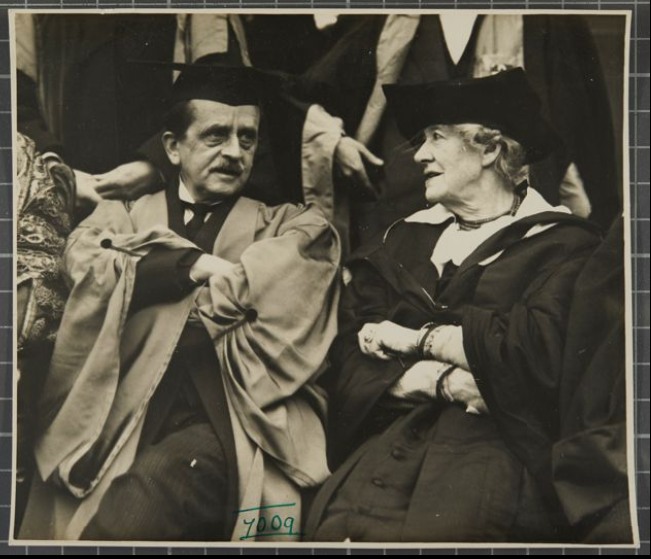

The story of Peter Pan and his creator, JM. Barrie, are celebrated in the Wardlaw Museum collections. This statue of Peter Pan, created by George Frampton, was gifted to St Andrews’ students residing in University Hall in 1922. This was to mark Barrie’s time as Rector of the University of St Andrews. Barrie was made Rector of the university in 1919 and served until 1922. In this time, Barrie advocated for female equality, suggesting his successor should be Dame Millicent Garrett Fawcett, and relentlessly championed the student voice as one to be listened to as the voice of the future. Barrie gave many notable lectures and addresses, inspiring and entertaining students and the wider community, discussing courage and cricket, friendship and the future. His most notable delivery on these themes was his Rector’s address in 1922, titled “On Courage”. Nearly a century later, his words still hold true and are valuable to any St Andrews student, especially one stepping out into the world in a time as turbulent as this. In “On Courage”, he warns:

“Learn as a beginning how world-shaking situations arise and how they may be countered. Doubt all your betters who would deny you that right of partnership.”

Following a war that would take thousands of lives, including many from St. Andrews – certainly, in 1922 there would have been many listening that felt the gap of a brother or father lost to the war – Barrie called for mental vigilance, a skill that a century on that has become more ever more necessary in a time of uncertainty, and for many, isolation and loss. It is somewhat unsettling to appreciate how timely his words are in a climate of relentless news and propaganda, and it is worth heeding his advice to “question, question, and question again”. Barrie implored the students of St Andrews to pursue truth, not only in what they sought through learning but also within themselves and their peers:

“… Know what you mean … We do not discuss what they say, but what they may have meant when they said it …”

In the darkness of this chaos and turbulence however, JM Barrie expresses hope, and a belief in the future generations that they can express the courage they need in these times. He tells the students:

“My own theme is Courage, as you should use it in the great fight that seems to me to be coming between youth and their betters; by youth, meaning, of course, you, and by your, betters us. I want you to take up this position: That youth have for too long left exclusively in our hands the decisions in national matters that are more vital to them than to us. Things about the next war, for instance, and why the last one ever had a beginning. I use the word fight because it must, I think, begin with a challenge; but the aim is the reverse of antagonism, it is partnership. I want you to hold that the time has arrived for youth to demand that partnership, and to demand it courageously. That to gain courage is what you came to St. Andrews for.”

Again, JM. Barrie’s words ring out as true and relevant nearly a century on. The students who have graduated from St. Andrews this month, like those who did in 1922, are graduating into a world of uncertainty. But they are also emerging into a world full of promise, and opportunities to learn from previous generations and better the world, both for themselves and for those who come after them. Barrie’s words encourage the new generation to maintain the optimism and energy of youth, as they work together to build a better future for all.

Words by Mia Foale