Willa Muir, International Women’s Day

This International Women’s Day I’m thinking about what it means to try to write about, and on behalf of a group, a form of feminist practice that historically, was received, if not without criticism, at least with a sense that to do so was to try to improve things or prevent them from getting worse. To intervene, in other words: to become involved intentionally in a difficult situation or debate to try to make it better or prevent it from worsening.

Once upon a moment in history, it seems to me anyway, we accepted more readily that a voice, attempting to speak on behalf of many other voices–some silenced, some less inclined to noise, some unable or even unwilling to articulate the problem–was a positive intervention. Now, with the immediacy of social media, even a voice mediated by an awareness of intersectionality is often savaged by anonymous trolls, and left as so much carrion, to be picked over by journalists, who wonder out loud what it is about the internet that so provokes a dark desire to hurl abuse at strangers.

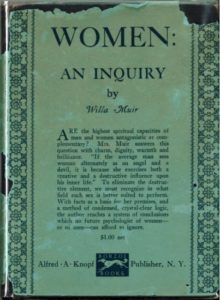

I was asked if I would write a blog post about Willa Muir’s Women: An Inquiry for International Women’s Day, as the University holds a first edition copy which will feature in the new thematic galleries of the Wardlaw Museum when it opens in April. Willa Muir (1890-1970) studied Classics at the University of St Andrews, and Educational Psychology at Bedford College, before becoming a teacher, translator, novelist, cultural commentator, and latterly memoirist. She (with her husband Edwin Muir) would become the first translator of the fiction of Franz Kafka into English.

Muir is sometimes remembered as the wife and literary help-mate of the aforementioned poet Edwin Muir, a designation she struggled with, as recorded in her journal, letters, and memoir, Belonging (1968). An oft-quoted passage of her journal reads:

I am a better translator than [Edwin] is. The whole current of patriarchal society is set against this fact however and sweeps it into oblivion, simply because I did not insist on shouting aloud: ‘Most of the translation, especially Kafka, has been done by ME. Edwin only helped.’ And every time Edwin was referred to as THE translator, I was too proud to say anything; […] I am left without a shred of literary reputation. And I am ashamed of the fact that I feel it as a grievance. […] I seem to have nothing to build on, except that I am Edwin’s wife and he still loves me. That is much. It is more in a sense than I deserve. And I know, too, how destructive ambition is, and how it deforms what one might create. And yet, and yet, I want to be acknowledged.

Here is a familiar voice: a woman writer who worked hard her whole life to support herself and her husband, and who sacrificed much of her personal presence to that project. A woman whose commitment to the feminist cause was repeatedly circumscribed by the circumstances she found herself in, professionally and personally.

Her publication, in 1925, of Women: An Inquiry, with Leonard and Virginia Woolf’s Hogarth Press, met with almost no critical response, and very little press attention. Since then it hasn’t gained much by way of a recuperation either, and there is good reason for this. Kirsty A. Allen begins her introduction to Imagined Selves (1996), an edited collection of Muir’s two novels and three cultural essays, by explaining that Women: An Inquiry is ‘entertaining’ if ‘unconvincing’, and that, in light of modern feminist thinking, it ‘seems sadly dated and misguided’.

I am inclined to agree with Allen that Women: An Inquiry is not Muir’s finest work. If published today it might slot neatly into what has been dubbed the ‘tradwife’ movement, a social-media-driven trend whose hashtags include: #tradwife, #tradfem and #vintagehousewife. Allen elaborates: ‘ the work is an unconscious endorsement of the patriarchal system which had kept women in the home–and in the submissive position against which Muir constantly rebelled’.

It could, therefore, appear to be an odd choice of text to highlight on International Women’s Day, except that Muir’s essay, like her commitment to feminism, is a sum of contradictory parts, some progressive, some remarkably not. And so it seems like enough of an intervention, to me, on International Women’s Day 2020, for us to listen to a little heard voice; to remember a ‘forgotten’ piece of feminist writing; and to acknowledge the literary work of Willa Muir.

Excerpts from Women: An Inquiry:

“Men and women share jointly in what is called human nature, and are alike capable of courage, fear, cruelty, tenderness, intelligence, and stupidity. When exhilarated by power and responsibility they display the more dominating qualities, and in subordinate positions they manifest a ‘slave psychology’”.

“In a masculine civilisation the creative work of women may be belittled, misinterpreted, or denied: but if it is a reality, its existence will be proved at least by the emotional colour of the denial”.

“Every great man has been inspired by some woman. The hand that rocks the cradle indisputably rules the world. A woman was the first cause of original sin, but a woman was the Mother of God. What does this mean? Half of the picture is tinged with vague contempt, and the other half with vague reverence. Apparently the average man sees woman alternately as an inferior being and as an angel”.

“One must conclude that he is looking at her through a distorting medium. His conception of her as an inferior being is natural, in a man-made State, and were she really inferior it would stop there. His vague reverence for her remains to prevent this conclusion: it is certainly a compensation for something, a distorted recognition of some half-guessed-at power in women. It looks as if man knows that the inferiority of woman is a fiction, that his domination of her and his refusal to admit her to his own level are not justified. In the background there lurks a fear of reprisals. The distorting medium contains fear as one of its elements”.

“It can be inferred that a fearless attitude towards human life is the first essential quality of a free woman, and that conventional morality is imposed with such emphasis upon women because the creation of moral values is their own peculiar vocation. Men are more concerned to prevent women from having untrammelled judgment and action in affairs of morality than from having access to the possession of wealth. In other words, women are hindered not only from external power, but from the inward power of creating independent moral and religious values. It is precisely this power which is exercised by creative women in their treatment of others, and the conventionalised ideal of the ignorant good woman is the deepest disability laid upon women in a men’s State”.

“The first condition that is required from women is that they shall know themselves. A woman who is ignorant of her own weaknesses cannot help others, for she is incapable of correcting distortions caused by her own fear or anger. The conventional woman hangs conventional ideas between herself and her own nature, thus negating her deepest instincts. She despises and represses part of her own humanity; consequently she has a repressive instead of a fostering effect on other people. Women must therefore be frankly sincere with themselves if they are to be creative, and must make allowances for their own faults in dealing with others”.

“The whole world needs creative women, and seems to be unaware of its need. Women themselves do not know how necessary they are. The result is that many waste themselves in trying to be men, and many are content to justify their existence by simple drudgery”.

“It looks as if during the next few generations the really creative New Woman will emerge, for conventional morality is no longer so powerful among women, and they are gradually deserting the blind alleys into which they rushed in their first efforts at self-assertion”.

“Even to-day, especially in politics, men find it difficult to rid themselves of the uneasy suspicion that women are dangerous”.

Dr Helena Goodwyn

Lecturer in English Literature

School of English, University of St Andrews